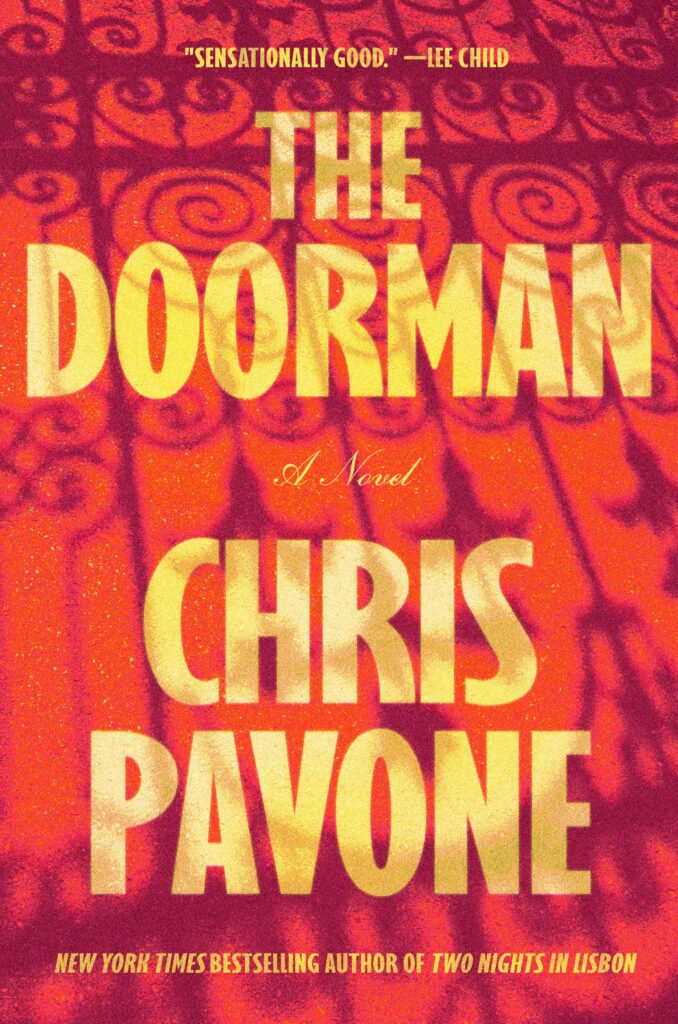

Award-winning novelist Chris Pavone has been transporting readers around the globe with his jet-setting thrillers Two Nights in Lisbon, The Paris Diversion, The Travelers, The Accident and The Expats. In The Doorman, launching May 20, readers stay firmly planted in New York City, but soon realize that the city’s multi-layered social hierarchies are truly worlds apart.

Northforker sat down with Pavone, who splits his time between Manhattan and Orient, to learn what drove the writing of this social satire with a dash of thriller page-turner, and why it’s being called a Bonfire of the Vanities of its time.

Northforker: This book feels different from your others in both pacing and plot. What’s the overarching story and what prompted you to tackle such sweeping topics as race, class and ambition?

Chris Pavone: I’ve always loved New York novels—Invisible Man and [author] John Dos Passos, Bright Lights Big City and Jazz , Jonathan Letham and Richard Price, Pineapple Street. In the best of these books, the city isn’t merely a setting, it’s a confluence of themes—race and class and money, art and commerce, ambition and crime, sex of course, and the thing that New York City people love to talk about above all other subjects: real estate.

A few years ago my family moved into a fancy apartment house on Central Park West, where I got to know some of the doormen, and one guy in particular who spent his entire working life in this one job, at this one place, until just a couple of days before he died. He and I lived very different lives, but we converged in a place and time where one of us worked, and one of us lived. That was something I wanted to explore, in the context of many different types of conflict—marital conflict, moral conflict, mortal conflict.

NF: Bonfire of the Vanities, set in the ’80s, was also a scathing look at social strata in New York City. Fast forward to 2025. What’s different now, if anything? Why is today’s climate ripe for The Doorman?

CP: Back in the 1980s, we may have disagreed about the viability of trickle-down economics, or the wisdom of arms-racing the Soviet Union to death, but we did agree on the fundamental facts of the world, as presented to us every evening by the network news. Today, the media are so fractured that they seem to occupy completely different realities, which I think has caused us to hate each other a lot more than we used to, even among people who agree on 99 percent of everything. We’re now much more sensitive to our physical identities—racial identities, gender identities, sexual identities—but I think much less attuned to our class identities, to our shared interests. It’s no longer easy to answer the question of what it means to be liberal, conservative, democrat, republican. Who gets to decide?

The Doorman tackles all these issues in the background. But in the foreground it’s a suspense novel that takes place almost entirely in one tense, fraught, perilous and ultimately fatal day and night, in a microcosm of the conflicts that permeate America at this moment.

NF: No one was spared in the details and social commentary. Did you have fun creating all these character studies?

CP: Bonfire of the Vanities was a spectacularly entertaining novel that skewered everyone, but some of it doesn’t hold up all that well—it’s a book about racism that is, arguably, pretty racist itself. I wanted to write a similar type of suspense novel that’s more attuned to today’s sensitivities, while also being a book about those sensitivities, or over-sensitivities, a lot of which are vested in The Doorman’s minor characters. I really love the three main characters, I love their relationships, I love their problems, I love their failings, I love the momentous choices they make at the end of their intertwined stories.

NF: You grew up in Brooklyn and now live in Manhattan. Were you always intrigued by apartment microcosms and the Upstairs/Downstairs secrets of inhabitants and staff?

CP: I’ve always been intrigued—astounded—by everything about New York City. Look around any crowded subway car, it’s a miracle of diversity. This is one of the defining traits of big cities in general, and of New York in particular, all of us thrown together—religions, ethnicities, ages, economics, professions, sexualities. In fiction, this creates opportunities to explore the ways in which our humanities overlap, and diverge, and that’s how I hope everyone reads the novel. That’s how I hope everyone reads every novel; that’s what novels are for.

NF: As a New Yorker, how much of your lived experience comes through to your characters? (i.e. riding the subway in a tux)?

CP: One of the characters in The Doorman travels by subway or bus whenever he puts on a tuxedo, and so does the book’s author; it makes me feel less like a jackass than being driven around in a black car in black tie. This same fictional character also suffers from many of the same complaints—physical, metaphysical, existential—that I do, while living in a similar apartment to mine, in a similar building. This character is definitely not me, he isn’t based on me, but all my characters—men, women, major characters, minor—have little bits of me in them — especially my worst attributes! — as well as bits of of real-life stories I’ve heard, of conversations I’ve overheard.

NF: Where do you like to write when you’re here on the North Fork?

CP: I often write on my front porch, watching the world go by; I’ve discovered that I need the occasional distraction in order to concentrate. Or under the attic eaves, where my desk sits in a window with views of the water. I also like to get away from the house to work, mostly at Aldo’s in Greenport, but my favorite spot is the wharf in Orient, on a nice day in summertime, during the kids’ sailing program. There’s not much in the world that’s cuter than a flock of little 8-year-olds setting out into the harbor in their little boats. For a decade I spent all summer every summer with my kids on the North Fork—playing baseball, beach walks with the dog, cooking for the various small people who made their way to my house at mealtimes. But my children are in college now. I miss them, and I miss that summer life. It’s something that looks like it’s going to last forever, then one year it just ends, forever.

NF: Any North Fork spots you love to frequent for inspiration or just to unwind in general?

CP: Orient is magical. I feel myself unwind even as I’m still driving east over the causeway, with the Sound on one side and Orient Harbor on the other, Bird’s Eye hill rising to the left and the village’s shoreline spreading out on the right, the egrets stalking in the water and the ospreys lurking above—it’s a vista that’s stunning in every weather, in every season, like living in a national park that’s also filled with beautiful houses and people I love and great food.

NF: Any plans for a Chris Pavone thriller set on the North Fork? Or the East End in general?

CP: There are already scenes in two of my novels that are set on the East End, both forks. My grandparents had a house in Cutchogue, and I’ve been spending time here in seven different decades. The North Fork has changed immensely during those years, and I have an idea for a suspense story that takes place entirely in a village here, exploring the tensions of the evolution.

Chris Pavone’s “The Doorman” is available for sale at Burton’s Books (43 Front St., Greenport, 631-477-1161), where he will be doing a reading and signing on May 31, as well as at these local spots: Saturday, June 7 at the Shelter Island Public Library (37 N. Ferry Road, Shelter Island, 631-749-0042); Friday, July 18 at the Hampton Library (2478 Main Road, Bridgehampton, 631-537-0015); and Friday, Aug. 9 at the East Hampton Library’s Author’s Night.