Discovering a species that has inhabited this planet for about 400 million years is a core childhood memory for many adults who grew up on the East End.

It’s becoming increasingly less common, however, for the current generations searching the shorelines to stumble upon horseshoe crabs—or what some local educators call our coastline’s “unsung hero.”

The species’ population—creatures that have survived for nearly 500 million years on this planet, pre-dating dinosaurs—is now at a vulnerable point due to habitat loss and overharvesting. New York State’s Wildlife Action Plan, updated every decade, listed horseshoe crabs this year as a “Species of Greatest Conservation Need.” Several local champions are trying to change that status.

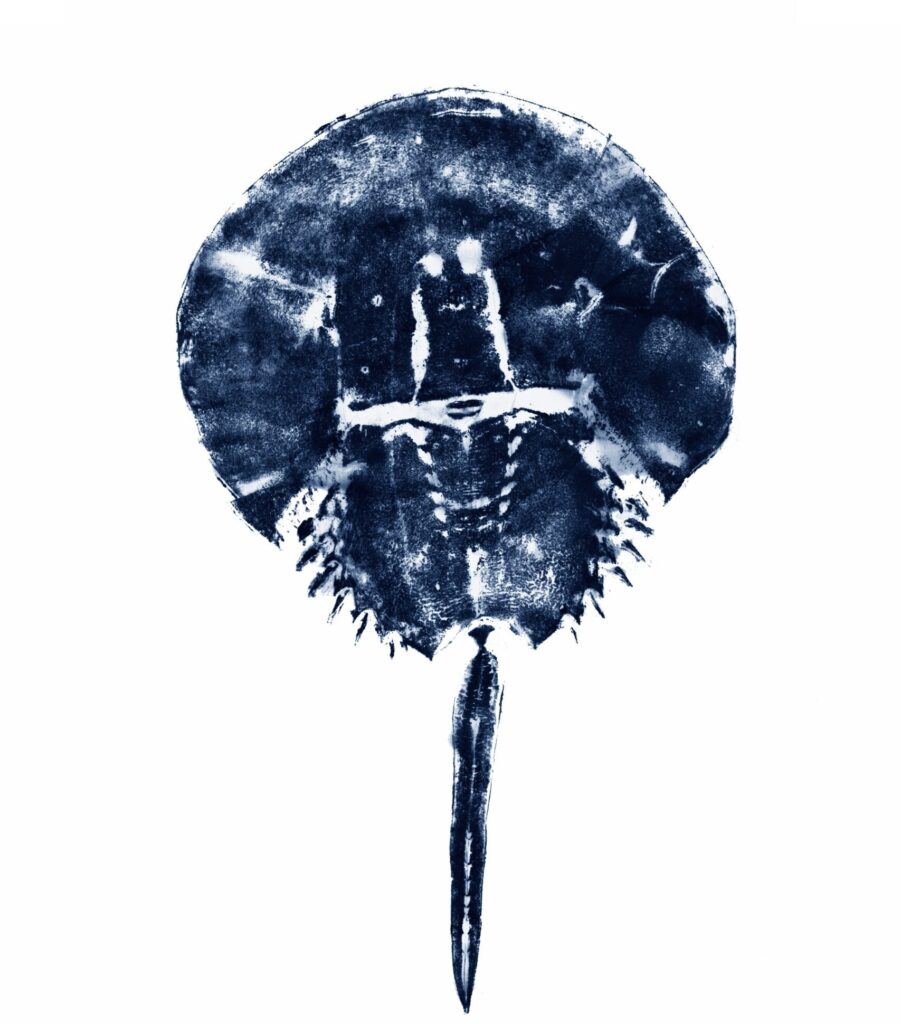

(Exo)Skeleton Crew

The horseshoe crab that so many Long Islanders know and love is a species specific to the United States, found along the East Coast in the Atlantic Ocean. It sports a hard exoskeleton with 10 legs and lives in deep, salty water until reproduction starts in late spring and early summer.

“Horseshoe crabs are currently still prevalent in New York waters but have shown an overall decline in the Long Island Sound, Jamaica Bay, Peconic Bay and Western Long Island,” the Department of Environmental Conservation, the governing body for horseshoe crabs, wrote in the 2025 Action Plan.

Developed in 1970, the DEC is a culmination of all state-designed environmental protection and enhancement programs pulled into a single entity. It sets horseshoe crab fishing limits—published at dec.ny.gov—and works with Cornell Cooperative Extension to monitor and research the marine invertebrate. Regulations and quotas are established by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, the overseer of all Atlantic fisheries.

New York horseshoe crab commercial harvesters faced lunar closures in May and June. The managed species—which is limited to 150,000 crabs total in New York State for 2025—is protected from being caught around select new and full moon phases, during horseshoe crabs’ reproductive period.

“They’re a keystone species, which means that they’re very important in the ecosystem and the food chain and other species truly rely on their eggs, specifically shorebirds, for survival,” says Jennifer Hartnagel, director of conservation advocacy for the Group for the East End, based in Southold and Bridgehampton.

Hartnagel was an advocate for 2024’s Horseshoe Crab Protection Act, a bill brought before New York State Gov. Kathy Hochul to ban the commercial harvesting of horseshoe crabs for bait and biomedical purposes, the two most common uses for the species. Horseshoe crab bait is used to fish for eel and whelk, and their blood is used for bacteria detection in the biomedical field.

“The legislation passed the Assembly and the Senate with flying colors and to become a law the governor has to sign it,” says Hartnagel. “[Gov. Hochul] vetoed the bill in December of 2024, effectively ending that piece of legislation.”

According to Hartnagel, the bill had tremendous public support, with almost 30 organizations backing it. In her veto letter, Gov. Hochul said she felt the management of horseshoe crabs was better left to the DEC’s discretion, relying on planned lunar closures to address population concerns.

“This bill could have unintended consequences on the management of other species such as whelk and eel, and could harm the commercial fishing industry and impair advancements in the biomedical field,” Hochul wrote in the letter.

Hartnagel is lobbying to get horseshoe crab legislation passed in the next session.

“Nothing has changed in our opinion,” she says. “We feel strongly that the science is on our side and the writing is clear that this is a species that is truly in trouble. If we don’t do something now, we might not have that chance in the future.”

Follow That Crab

There’s reason for hope up and down the East Coast, with neighboring states seeing the wisdom and valuing the forethought in protecting horseshoe crabs. Connecticut passed identical legislation to the kind proposed in New York in 2024, and New Jersey has a moratorium on the harvesting of the species.

“Since we share the [Long Island] Sound, it’s a shared water body, we should get on board with a unified management strategy to manage this species for conservation purposes,” says Hartnagel.

There are other reasons to feel optimistic, too. Currently, no biomedical harvesting licenses have been issued in New York, halting that population impact factor.

Matthew Sclafani, a marine educator at Cornell Cooperative Extension, is a leader in the horseshoe crab monitoring program across Long Island. The DEC-funded initiative has been collecting data on the species since 2007.

“We’ve been getting pretty high-quality data since we, Cornell Cooperative Extension, designed the program, to specifically be meeting the needs of Long Island,” Sclafani says.

Monitoring began at three different Long Island locations and has since expanded to 30, from Fishers Island to Staten Island. Site coordinators and trained volunteers use scientific methods to count and tag crabs for 12 nights around new and full moons in May and June.

The initiative’s research is just coming up on enough years’ worth of data to provide viable insight into horseshoe crab migrations and populations. Sclafani says the DEC looks for 12 to 15 years of numbers.

Hazel Wodehouse is another marine educator at CCE, as well as a volunteer coordinator at Back to the Bays, a CCE initiative that provides community opportunities for local marine learning and involvement.

Wodehouse, who developed a fascination with the marine species as a child, served as site coordinator for horseshoe crab monitoring at Tiana Bay in Hampton Bays. Before becoming a leader, however, she was a site volunteer.

“It was inspiring,” she says. “It made me feel like I’m actually collecting real scientific data that’s going to something much bigger than myself and much more long-term.”

Recently, Wodehouse moved to Massachusetts, continuing her role with CCE remotely, exploring an unfamiliar coastline.

“I’m starting to understand how unique of a situation Long Island is in,” she says. “The number of marine habitats and the diversity there is incredible.”

By the Numbers

Despite the extensive marine life in New York, Wodehouse is aware the population of one of her favorite species is in decline.

“There’s this concept called the ‘shifting baseline,’” she says. “If no one was here to teach me how many horseshoe crabs used to be out there, and I went out and saw 30 horseshoe crabs in one night, I might be like, ‘Whoa, that’s so many horseshoe crabs.’ But if I should be seeing a thousand—that’s what was normal 10 years ago—I have no way of knowing that.”

Pete Topping, executive director and baykeeper at Peconic Baykeeper, grew up on the East End and serves as site coordinator at Meadow Lane in Southampton in partnership with South Shore Estuary Reserve. He focuses on outreach, getting local schools and organizations involved in horseshoe crab monitoring.

In the past, when he’s shown up to the site for monitoring based on the reproduction calendar, harvesters have monopolized the horseshoe crab population, leaving nothing to count or tag.

“When wildlife is breeding, that’s when you want to protect it,” says Topping. “For something like horseshoe crabs, when they’re coming up on these beaches, when they’re literally crawling out of the water in sometimes giant aggregation, it’s very easy to harvest that.”

Despite the challenge he faces as a site coordinator, Topping acknowledges that a balance must be found between supporting the species’ population and providing access to industries that rely on the invertebrate.

“In an ideal world, there might be an artificial bait or full-on ban,” he says. “But I think when you want to get support for these things, it’s hard when essentially banning that would wipe out some livelihoods for some local baymen.”

One way to even the playing field would be limiting the sale of the species, Topping suggests, restricting baymen to harvesting for their own whelk and eel traps as opposed to commercial harvesting, and banning the harvesting of tagged horseshoe crabs to ensure better accuracy in the monitoring process.

It remains unclear what the future holds for this species, but there is no denying East Enders’ personal connection to the horseshoe crab.

“I do think there’s a really big importance in continuing to tell stories,” says Wodehouse, “and to have this data.”